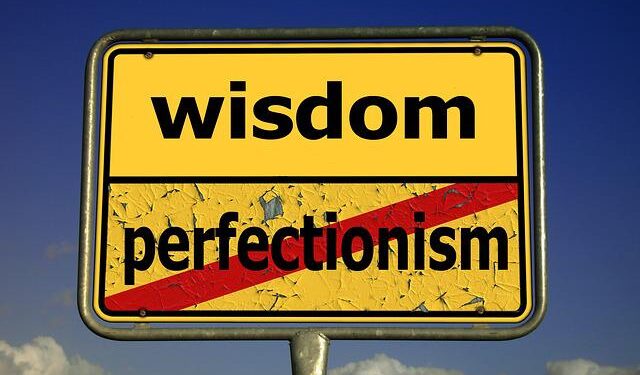

Physician perfectionism and burnout are inextricably linked. Perfectionism in medicine is an unhealthy delusion that fuels not just burnout but mental illness and suicide in doctors. In this article, we explore the concept, causes, and dangers of perfectionistic thinking and behavior in doctors.

The practice of medicine is rapidly changing and causing significant stress for physicians around the globe. Examples of these stressors include: the loss of autonomy associated with hospital-based practice, the restrictions on practice associated with managed care, the ongoing escalation of liability lawsuits, and the maintenance of competency in a rapidly changing specialty.

These stressors can interact with pre-existing psychological characteristics typical of doctors which can lead to burnout and worse.

Writer Anne Lamott is quoted as saying: “Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor; the enemy of the people. It will keep you insane your whole life.”

Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor; the enemy of the people. It will keep you insane your whole life -- Anne Lamott

All doctors have some degree of perfectionism: after all, meticulous attention to detail and the wish to get things right are desired characteristics.

As described by Glenn O. Gabbard MD in in 1985, doctors can also develop a cognitive triad of doubt, guilt, and an exaggerated sense of responsibility. This triad manifests itself in both adaptive and maladaptive ways.

Maladaptive ways include difficulty in relaxing, reluctance to take vacations from work, problems in allocating time to family, an inappropriate and excessive sense of responsibility for things beyond one’s control, chronic feelings of “not doing enough,” difficulty setting limits, excessive guilt feelings that interfere with the healthy pursuit of pleasure, and the confusion of selfishness with healthy self-interest.

Healthy perfectionists set high standards for themselves but drop or moderate these when required.

Healthy perfectionists can maintain a big picture perspective, look at alternative views, and manage their sense of responsibility for others. They don’t get too upset if they don’t quite meet their goals, they focus on the positive which motivates performance, but not at the expense of their own mental health.

Unhealthy perfectionists on the other hand, are unable to change perspective or moderate their own high standards.

Doctors are expected to maintain high standards and perform flawlessly. The first is a reasonable expectation; the second is not because no-one is perfect.

Patients, doctors themselves, and healthcare organizations demand that physicians never make mistakes. There is a reason why doctors are continuously the most trusted profession. Yet doctors themselves are part of the problem in expecting perfectionism in themselves and sometimes their colleagues and systems.

The nature of medicine, combined with doctors’ tendency to internalise high standards, means that we’re inclined to work harder, achieve more, give more to our patients, and deny our own needs.

As with anything, physician perfectionism can be unhealthy if taken to an extreme. Maladaptive perfectionism is characterized by excessive preoccupation with past mistakes, fears about making new mistakes, doubts about whether you are doing something correctly and being extremely concerned about the high expectations of others, such as parents or employers. An excessive preoccupation with control is a hallmark feature of maladaptive perfectionism.

The etiology of medical perfectionism is both internal and systemic.

Internally, medicine selects for people with high standards and a strong work ethic. Often in order to obtain the results to get into med school, would-be doctors have to show rigorous discipline and hard work. Having perfectionistic personality traits drives hard work, attention to detail, and concern to “get things right” – all desirable medical traits.

We score high on personality assessments of competitiveness, perfectionism, anxiety, and high goal-orientation. All of these are significant components of what Meyer Friedman, MD, defined as the “Type A Personality.”

We Type A people are opinionated, judgmental, and pressured to succeed. We are chronic multi-taskers, always in a hurry, and poor at delegating.

Doctors are trained to never make mistakes, so when they do occur, they may be tormented by their own sense of perfectionism, resulting in self-incrimination and even self-loathing. An exaggerated sense of responsibility coupled with guilt and self-doubt adds stress to an already difficult situation.

Arguably, medical perfectionism is tolerated in small doses. But, as with any drug, sustained high doses increase the risk of adverse effects.

Externally, perfectionism starts before medical training by selecting high-achieving people with high standards. Medical training is highly dysfunctional. It exaggerates the traits we have, typically at the expense of compassion, sensitivity, and social connection.

The healthcare system demands perfect doctors and does not tolerate error. We may not miss a diagnosis, miscommunicate with our patients, or operate on the wrong site. Given the sheer volumes of clinical interactions, some of these are sadly unavoidable to a small percentage of unlucky patients (and doctors). These systemic factors increase the expectations of patients – and indeed their lawyers and the courts.

Politicians, scientists, and industry also must take some of the blame: promising unrealistic cures to cancers, or universal low-cost medical care, all worsen unrealistic patient expectations which in turn fuel the frankly obscene amounts of malpractice litigation, doctor-bashing, and unnecessary stress upon the profession.

The illusion of the perfect physician is hurting us.

The odds of being sued at least once over one’s career are high and the US is notorious for its soaring levels of medical malpractice litigation. Absurd cases get shared with shock and relief by doctors outside the US — relief that it hasn’t happened to them. In very few other countries is “Ambulance-chasing lawyer” a profession.

Further, when things go wrong, and they will, the system is unforgiving. Some leaders pay lip service to “no-blame cultures” and “no-fault investigations”, but in the experience of many physicians, if a scapegoat can be found and blamed, it will.

What if you wake up some day, and you're 65... and you were just so strung out on perfectionism and people-pleasing that you forgot to have a big juicy creative life? - Anne Lamott

Perfectionism in small doses ain’t bad when it leads to improvements in clinical care — but only if it does so without driving doctors to despair.

Yet, as I have argued elsewhere, perfectionism among other personality traits is a double-edged sword. While it can motivate us to higher levels of skill and achievement, and obsessional checking of swabs and O2 levels reduce patient risks, it can also lash back with self-criticism, fear of failure, black-and-white thinking, and poor self-compassion.

Our own high standards can be translated to others who, also being human, invariably fail. Our own frustrated or angry reaction can cause work relationship strain when what we need is comradeship and teamwork.

Perfectionist physicians typically suffer from various cognitive distortions: that they are valued only for their performance; that the better they do, the better they are expected to do; and that, if they lose the “edge,” they will lose their colleagues’ support.

Perfectionistic personality traits, also called neurotic or obsessional traits, have been repeatedly linked to worse mental health in physicians.

Perfectionistic personality traits, also called neurotic or obsessional traits, have been repeatedly linked to worse mental health in physicians.

The consequences of this perfectionism include only short-lived satisfaction with achievements; a sense that awards and accolades are unmerited; and striving to excel not for personal and professional satisfaction or pleasure, but rather to relieve the tormented psyche.

Perfectionism is one of the major precursors for burnout because it is often accompanied by an exaggerated sense of responsibility that leads to self-doubt and guilt, which then lead to rigidity, stubbornness, and the inability to delegate. These behaviors, in turn, may result in a devotion to, and identification with, work to the exclusion of relationships and self-care.

Perfectionism is also one of the predisposing factors for suicide because fear of failure provokes the need for complete control of everything in a physician’s professional and personal lives, which can leave us feeling empty, disconnected, and cynical.

In this article, we have explored the concept and dangers of perfectionistic thinking and behavior in doctors. We have linked perfectionism in physicians to burnout and mental illness and listed the internal and external causes.

In Part 2 we will explore Solutions to Physician Perfectionism (Coming soon).